NASA’s proposal to add astronauts to the maiden flight of its new Space Launch System could have humans flying on a Decatur-made rocket as early as next year.

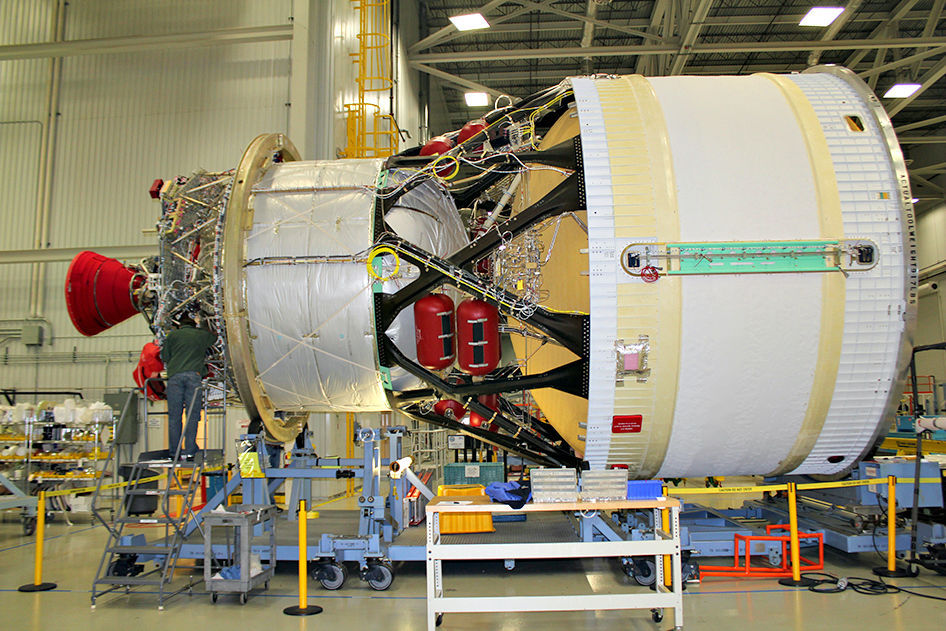

United Launch Alliance confirmed this week it is nearing completion of its Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, or ICPS, at its Decatur manufacturing facility.

The ICPS will serve as the second stage of the Space Launch System, or SLS, during its maiden flight slated for November 2018.

A ULA spokeswoman declined to release a precise departure date for the ICPS from Decatur, citing safety concerns, but said it would be transported by barge to Cape Canaveral, Florida, where it is due early next month.

The maiden flight of the SLS was intended to be an unmanned trip around the moon to test critical systems during the first integrated flight of the new launch system and the Orion spacecraft that eventually will carry astronauts to Mars.

But NASA announced this month it is studying the possibility of adding a crew to the mission, accelerating the pace of the program, which was not planned for human flight until 2021.

“The study will examine the opportunities it could present to accelerate the effort of the first crewed flight and what it would take to accomplish that first step of pushing humans farther into space,” NASA officials said in a statement.

The Orion spacecraft has flown before — launched atop a ULA Delta IV in an unmanned test flight in 2014 — but next year’s flight will be the first time the SLS has flown.

Adding crew to the mission will require the ICPS to be safety rated for humans. The component is based on the second stage of ULA’s Delta IV rocket, which was not designed for manned flight.

The ICPS is a stopgap in the program to be used until the final propulsion stage of the SLS is fully developed.

Asked about the challenge of certifying the component for a manned flight, ULA spokeswoman Lyn Chassagne said they stand ready to support NASA and other mission partners during the feasibility study.

“NASA’s announcement on possibly flying crew on the EM-1 mission is exciting for NASA and our country,” she said.

Once completed, the SLS will have the capacity for a 77-ton payload. Later versions will scale that up to 143 tons, almost comparable to the heaviest Apollo missions.

“The reason they need all that lifting capacity is because eventually, in the 2030s, the plan is to send astronauts to Mars,” said Loren Thompson, a defense analyst for the Lexington Institute and a consultant for Lockheed Martin Corp., one of ULA’s parent companies.

Thompson said the SLS relies upon fairly mature technology refined from the Space Shuttle program, so adding crew to the mission probably isn’t pushing the safety envelope too much.

The first mission next year and second mission in 2021 are designed to test the SLS and Orion spacecraft in maneuvers and environments they may see on a journey to Mars.

Crew size has not been determined, but the capsule can accommodate four to six astronauts.

The program will give America the capability to put astronauts in space for the first time since the retirement of the Space Shuttle program in 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment